Lisa said, Go to the beach. I didn’t go that day - or that week - but eventually, after the summer was over, I got there.

I’m ready to talk about more than the stroke now, but the experience lives in me, shimmering like the silver threads in my hair.

Announcements and New Beginnings

Before we dive in, a few updates:

The Flow Transmissions: A new way to experience them is here!

Workshops: "Becoming Real" workshops will resume the last week of November. We’ll complete the last three weeks of Constellation, which paused in June, and start Bless Everything in January. Join as a paid subscriber to participate.

One-on-One Soul Coaxing: I’m resuming these deeply personal sessions. Find out more about booking and availability.

Hello, Dolphins

I am so enjoying this new way of sharing my journey with you—just sitting down to tell you what I’m observing, learning, and noticing as I’ve recovered from the stroke and subsequent (bit of1) brain surgery. I feel less like ‘the teacher’, more like a friend or even, a reporter. I’ve been touched by the comments and emails you send. And the cards! What a rare and special joy to open a paper envelope and find a colorful image, encouraging words - and little surprises, a feather, a pinch of glitter, a divination card.

Thank you for your gifts of playfulness. Of care and remembering. I love them all.

xxoo

Two weeks ago, when I woke up filled with energy, like I used to—ready to move, to create, to notice, and receive, ready to live - I was overjoyed. That energy stayed with me the next day. I feel myself returning.

And yet, I don’t want the old me back; I’m beginning freshly, as someone new, someone more integrated, who’s been through something transformative.

I am still rebuilding, gathering the pieces of who I was and letting them fall into new patterns without rushing to complete this puzzle. Every day, I watch where the pieces land, savoring the discovery.

I’m ready to talk about more than the stroke now, but the experience lives in me, shimmering like the silver threads in my hair. As I rebuild my strength and even surpass my pre-stroke capacity, it feels as though I’ve turned a corner—from healing to truly living.

I’m embracing how my body feels now, how I move. In physical therapy, I add extra reps to every exercise. They tell me to step up and lift my knee to my chest; I do, with both arms rising as if in celebration. My knee lowers, and I bow. Inside, I am a dancer, a yogi, a woman rediscovering herself as new parts emerge to meet life’s challenges.

After the stroke, I noticed gaps in my “puzzle” and new shapes—a heightened awareness that had actually begun three days before the stroke and is still with me. I can see more, sense more.

Three days before what I now call “being struck by lightning,” I experienced a strange gift: I could see my own bones. I closed my eyes in yoga class and saw my skeleton inside me, each bone moving with my movements. I watched the connection between my intention to move and the movement itself. I could “see the thought” and follow its response in my spine, arms, and legs.

I was so captivated that I did much of the class with my eyes closed, just to watch my skeleton dance.

In the following class, I wondered if it would happen again. Instead, when I closed my eyes this time, I felt a presence, a protective being around me. “I’ve got you,” she whispered. “I will move you through this.” I surrendered, letting her carry me.

For the next 40 minutes, I felt enveloped in a soft cocoon, within which I could do anything—lunges and backbends I hadn’t been able to attempt in ages. Even as I moved, I knew: I wasn’t doing this. She was.

Then, kneeling in Cobbler’s Pose with my back arched and arms extended, I felt a crunch. “Uh oh,” I thought, but I felt no pain.

Later that night, I woke with migraine symptoms—headache, nausea, disorientation—and assumed that the ‘crunch’ had triggered a migraine. I took an Advil and went back to bed.

Reflecting on this life-altering moment, I can see now how it had been building all along. For weeks, I’d been making choices that raised my blood pressure and added stress. It felt as if some inner force was pushing me toward a profound change. I’d been asking for a shift, praying for it.

One month before the stroke, I had launched my Becoming Real workshops, my first new program in years. I was thrilled to finally offer my full curriculum in an accessible, affordable format.

Two weeks prior, I had returned from Portland, where I’d immersed myself in my daughter’s world of vintage shops, gardens, and friends I’d only known through Instagram. I’d quit dairy, become “accidentally sober” without even realizing, and lost six pounds. My life was in motion, pulsing with a rhythmic hopefulness.

After the chaos subsided, the first thing I noticed was that I no longer cared about the past. My attachment to it, like the wine and occasional cocktail, had let go of me. I noticed, too, that I wasn’t afraid. Except for one night of terror after being told I had an aneurysm, I felt at peace. The stroke had been mild, without pain or impairment in my thinking or speech. Even the weakness in my right side was resolving quickly.

I felt silent inside. I felt silent outside. And that silence was extraordinary.

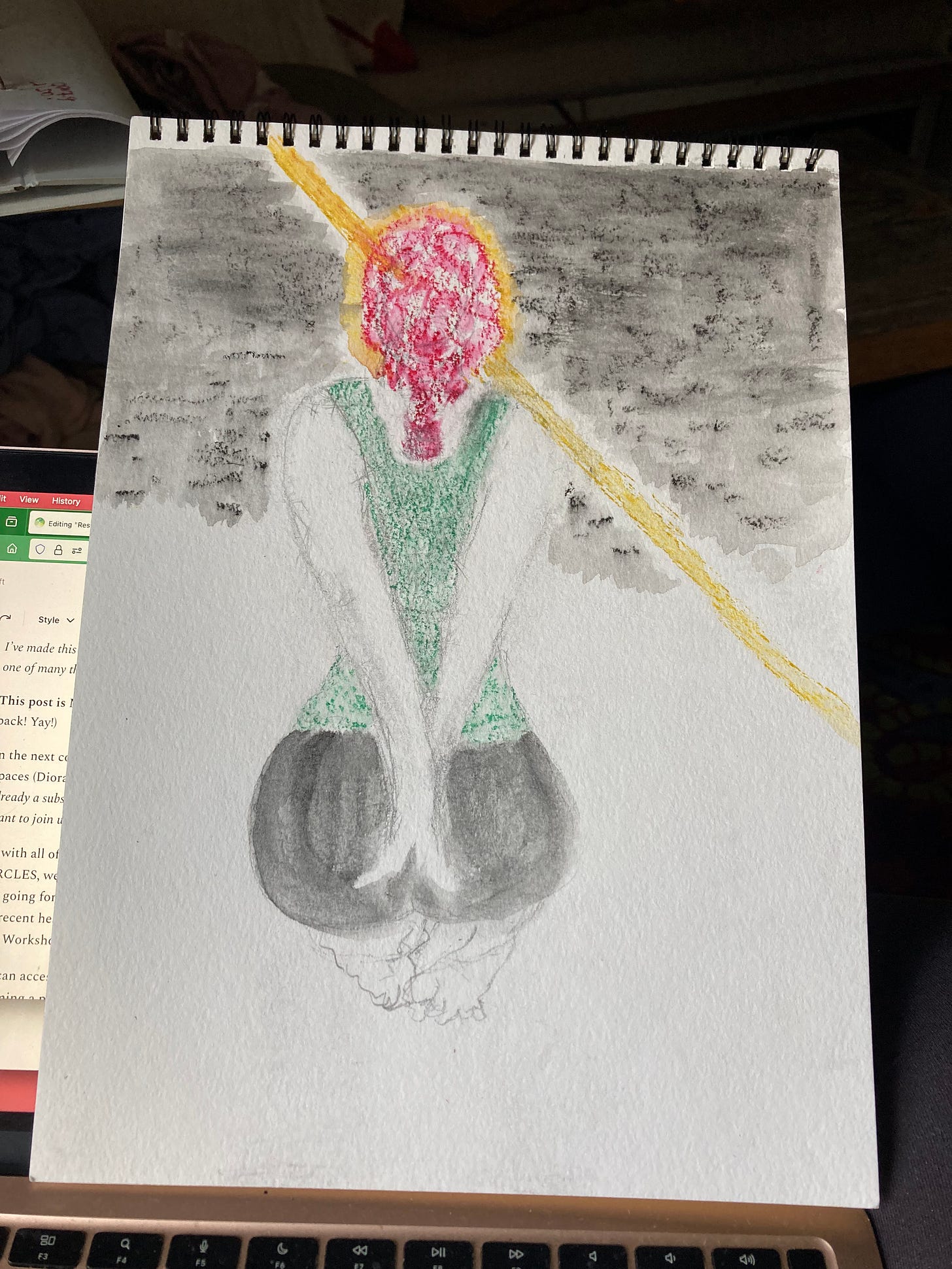

I made this painting in July, a few weeks after the stroke, as an attempt to capture the moment when I felt the crunch from inside the field of warm and glowing protection. It was a kind of padding. It was an aura, a field of love holding me. I don’t know what it was. Only how it felt.

My stroke was a lacunar infarction. “Lacuna” means a dent or depression, a divot in the landscape—an empty space, a missing piece in a puzzle. When I think of it now, I’m reminded of a vision I once had while leading a guided meditation for Journey.

We are inside our sanctuary tent, gathered around the campfire. Angels, Ancestors, and Guides have gathered to support us. We honor them, and we honor each other. One by one, we place our sticks of offering into the fire.

As I guide this meditation, I am also living it. I am there, in the tent, standing before the fire.

“Turn to the person to your left,” I say. “Hold out your hand. Imagine they place a small gift in your palm. See the gift. Notice its color, shape, and weight. Slip it into your pocket and offer your thanks.”

We turn to the right, becoming the gift bearer, placing a gift in the upturned palm of the person beside us.

“Step forward, into the center of the fire. Stand there, as the flames lick around you. You do not burn. This is an imaginal fire—the kind that can burn away the past, burn away doubt, shame, blame—all burdens. Let them fall. Let the past drop from you like a crust as you let go.

“Fall through the portal down to the world below, down to the solid ground. Cool and dry, supporting you. Nearby, you hear the gurgle of moving water—the underground spring that feeds our well. Rest here.

“You have entered a liminal space, slipping away from the world’s clock of ambition and activity, into a time out of sync, running on a different schedule.

This is the gift of a sacred interruption, a gap in the flow of things—a portal, a new kind of puzzle, an underground maze. Where will it lead?

Last week, I found a scrap of paper, torn from a notebook where, written in my own hand, there was a message. I am not inside of this body. I don’t remember writing this but I know that somewhen between the stroke and the brain surgery, I did so.

What could this mean? I wonder.

If I am not inside this body, where am I?

There are other notes like this, breadcrumbs, gleaming pebbles that I left along the path to guide me home or somewhere else. It isn’t clear yet where I’m headed. I am following the clues along a game board. Bits of puzzle stuff in a maze of surprises.

Earlier this month, I attended the first session of an in-person class on Carl Jung. A sweeping overview of the paradigm-shifting, scientist-artst, held at my beloved friend’s apartment. We removed our shoes by the door and turned a corner into a living room framed in bright windows, overlooking the Hudson River. Bathed in light, walls dancing with rainbows, we found thirteen chairs arranged in a circle.

On each chair, there was a book. Which would we choose? Love poems from Rumi? A book about art? I selected the seat where Maira Kalman’s Women Holding Things rested on a blue velvet cushion. I settled in. I lifted my eyes to the open circle of faces before me. Without a mute button or the option to hide behind a blank screen, I felt strange. Everyone was so real.

Later that day, “What do you want to talk about?” my therapist asks.

This question upsets me. If I don’t come with a list I feel caught in the headlights of some expectation. I feel like I am wasting money. Wasting time. I feel as if I have to live up to my potential. I blurt things I would rather not release into the world.

“I found a piece of writing in a journal just before our call.”

“What does it say?”

“Every time I land in my body, I sob.”

I imagine she will ask what I mean when I talk about ‘landing in my body’. I imagine she will ask about the sobbing.

Instead, she asks, ”Is it really every time?”

I am a woman holding things.

At the Jung class, the teacher handed out a sheet of quotes. “Mark the one(s) that speak to you,” she said.

These two were singing:

“To live oneself means to be one’s own task2.”

“If we are in ourselves, then the space around us is free, but filled by the god.3”

What does it mean to be in ourselves?

If we are not in ourselves, where are we?

This is the puzzle I am working on.

I am naming it: The Wild Good.

It has had other names (I’ve been working on it for years) but I find that, since the stroke and the embolization of the aneurysm, there is only one puzzle piece that needs placing: the small and often-imperceptible knowing

that I am good.

Some of this next part will feel like a diversion but it all fits together. We are building a puzzle out of words and memory. You just have to trust.

Last week, on the night of their wedding anniversary, my daughter-in-law texted: East Coasters — look out for the northern lights! I ran outside and there, in the sky over the farm was an undulating cloud of pink.

“Come see! Come see!” I called to my husband. I could not go inside to get him. I could not move from the spot where I stood beneath this marvel. He came and stood beside me and we marveled together. After the lights faded, we came inside and I wrote, on a scrap of paper, There are lights undulating in the sky across the road and, unless someone tells me to look, I am missing them.

I hid the scrap in the box that I keep now on my desk, full of messages from someone who knows how important miracles are to me.

Yesterday, I joined my husband on a drive to Long Island, the longest trip I’ve taken since the stroke. I almost didn’t go, but at the last minute, I thought: I can do this.

We crossed two bridges, sat in traffic, and arrived late—but it was glorious. His sisters were there, waiting at the Cheesecake Factory at the top of a long spiral staircase. I climbed it easily, silently thanking my physical therapists with each step. We slid into the booth, smiling and reaching across the table to touch hands. “I’m so glad to see you.” “You too.”

“I missed you,” my sister-in-law said, her eyes glistening with tears. “I missed you, too,” I replied, realizing as I said it that it was true.

After lunch, we spiraled back down to the parking lot. As I hugged each of them goodbye, it felt almost strange to have their bodies pressed against mine, to smell the familiar scents of their shampoo, detergent, and that unique “just you” scent each person carries. I realized I hadn’t hugged anyone in a very long time.

After brunch, on our way to Jones Beach, my husband told me about the house that he’s designing for Maria and Anthony. “It’s curved along the top like a woman’s body,” he said. “Two soft curves - one for the hip, one for the shoulder. As if she is lying on the ground, on her side. ” I have seen this house dozens of times and never once did I think that looks like a body. He said that the addition he was adding — a fantastical, whimsical two-tier wedding cake of a thing - didn’t fit. “The ruffle,” I called it and he looked at me. “It’s not a ruffle,” he said.

At the beach, we took off our shoes and carried them to the ocean. We walked, shoes in our hands, to the water. We trudged, carrying shoes to the edge of the sea. Halfway between the boardwalk and the water, I got stuck.

“The thing is,” I said, “I’m calculating the energy it will take to walk back.”

“You are halfway there,” my husband encouraged. “We will rest. We will sit and watch the water. You’ll make it back.”

After the beach, we went to Barnes & Noble, where, on a Sunday afternoon, every seat was taken. My husband gathered a stack of design magazines, and I made a pile of my own. We carried them to the second floor, where we sat on the floor, flipping through pages.

On the way home, he told me, “I think I’ve solved the puzzle. The addition has to complete the gesture. If this is the curve of a woman’s hip, and this is her shoulder, then the addition . . . it has to be her head.”

This morning, he showed me the drawing. Suddenly, it all made sense. I saw the curve, the hip, the shoulder—and, even though it’s just a house, I could see the suggestion of a woman’s head. “You did it!” I said, grinning. “It just looks right.”

My mother used to ask me, was I a good mother? I understand now why she asked. There are things that we regret doing. We see the results in our children. The shrinking from love. The insecure bonding. We imagine that we are the cause - if only we hadn’t said those harsh words. If only we hadn’t slapped, ignored, shouted. If only we’d been less exhausted, more willing to play one more game of Barbie or Risk or Chutes and Ladders. If only that thing hadn’t happened, the thing that broke the world we were trying to make perfect for them. The thing we can’t forgive ourselves for—the wound within our own hearts that we couldn’t keep down, where it couldn’t reach them. That dark part of us that, in a moment of frustration, exhaustion, and overwhelm, came screeching out of our mouth and into the light, breaking over our beloved, innocent child.

How do you heal something like this? How do you stop it from haunting you? Once it’s out, it finds a way in—to them, to the DNA, bone-deep and ancestral. It settles into the cells of things, spreading until it feels like it’s everywhere, impossible to undo.

My therapist says, “I think that you are fascinated with this pain.”

“I think I am putting together a puzzle.” I respond.

Later, I sit myself down and pretend I’m the therapist.

“What will you have when this puzzle is finished?” the pretend-therapist asks.

“Something that looks like a life,” I blurt. “Something that feels like I lived. It’s not about pride, fame, or success. I just want to complete something—a task, a sentence, to let a train of thought run all the way to the station.”

“What makes you think you’re supposed to finish?” my pretend-therapist asks, sounding just like my real therapist. “What if you set this project of finishing down? What if, instead, you worked on your garden?”

I went outside. I walked around the perimeter of my garden, which, over my summer of recovery, has been completely overgrown. “I like these grasses,” my husband says, running his palm across their feather tops. So do I.

This morning, I found another note, torn from an old sketchbook. It must have been important, but I don’t understand why. The upper left corner is missing, and the writing begins mid-sentence:

“. . . devotion to what?”

When did I write this? Before the stroke? After the brain surgery?

Halfway down the page, there are more words:

“. . . the image that I have is a person standing in a café.”

Is this a response to the question?

On the other side of the paper, I find more writing:

A person is just standing there when suddenly an invitation to another world emerges. A man collapses to the ground. A woman blurts out a sob story. A child falls into the water. And everyone pitches in. And everyone rallies round. And for one bright moment, everyone makes a choice to split open the known world and do something different.

I am putting together a puzzle made of sand. One grain begins to radiate, passing heat to the grain beside it.

To me, what stands out most about Carl Jung was his courage. He was frightened but he kept reaching, kept writing it all down. The endless flow of sensation, beauty, and offering. Jung let it shatter him. He let the silence, the fear, and the wild rising of the wild good move from the inside to the outside, and from the outside to the inside.

He allowed mysteries—both sacred and horrifying—to flow through his own body. He built himself a tower - and made himself into a container, a mishkan in the desert where he crawled in and lived. In a world that had set aside no place for such a journey, he made that place.

Also, he wrote it down for me. And for you.

This grief is a puzzle. This joy, too.

I was doing something. Now I am doing something else.

One cannot simply pivot.

One has to gather all the pieces, the edges are easiest - it’s the middle where you get lost. You’re supposed to get lost. This world has removed the markers and redrawn old maps—but none of those coordinates ever worked for me anyway. It’s a puzzle world that asks nothing of me but offers everything: the miraculous potential to build, and the terrifying potential to destroy.

“When will it end,” I ask my therapist.

“When you let it,” she says.

I use these disclaimers: a bit of brain surgery, a minor stroke because as these things go, my experience was not terrible. I did not suffer life-altering residual symptoms. I am as back to normal as I could have hoped when all of this began. So I find myself wanting to minimize all of it. Yesterday, my friend stopped me. “You’ve made remarkable progress,” she said. “Take that in. Why not be proud of what you’ve accomplished?” As I have said all the way through this experience, I don’t feel that I (Amy) have accomplished anything but my body certainly has.”

Both of my chosen quotes are from The Red Book, a red leather bound book in which Jung recorded his own depth soundings over a 5 year period. The first, “To live oneself means: to be one’s own task, has a particular resonance with my own journey .

It is part of a longer statement, which continues. Never say that it is a pleasure to live oneself It will be no joy but a long suffering, since you must become your own creator. If you want to create yourself then you do not begin with the best and the highest, but with the worst and the deepest. Therefore say that you are reluctant to live yourself. The flowing together of the stream of life is not joy but pain, since it is power against power, guilt, and shatters the sanctified.” (Carl G. Jung, The Red Book: Philemon)

"We should become reconciled to solitude in ourselves and to the God outside of us. If we enter into this solitude then the life of the God begins. If we are in ourselves, then the space around us is free, but filled by the God."

- Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 245

Jung described the process that led to the creation of the Red Book as “my most difficult experiment.” He was referring to his sustained response to a series of “assaults” from his unconscious that he feared might overwhelm him. These experiences began after Jung’s break with Sigmund Freud. Jung recorded them in a series of notebooks that he later used as the basis for the Red Book.

As he recalled in the autobiographical Memories, Dreams, Reflections: “An incessant stream of fantasies had been released . . . . I stood helpless before an alien world; everything in it seemed difficult and incomprehensible.’ Amidst this psychic turmoil, Jung resolved to “find the meaning in what I was experiencing in these fantasies”—a process that required him both to engage with and distance himself from their effect— and to describe, comprehend, and transform them for a constructive purpose.

The material in the Red Book came from Jung’s exploration of his unconscious and his encounters with the works of many cultural figures, including the pioneering American philosopher and psychologist William James (1842–1910). The format of the Red Book resembles the work of the British poet and painter William Blake (1757–1827), who also recorded dreams and visions in combined text and images and with whose work Jung had some familiarity.

Jung maintained that the experiences described in the Red Book were the foundations of the distinctive theories of his analytical psychology, saying, “All my works, all my creative activity, has come from those initial fantasies and dreams which began in 1912." As Jung refined his analytical methods, he developed the themes he first explored in the Red Book through study of Eastern and Western religions, psychological phenomena without scientific explanation, mythology, alchemy and physics, and the dreams of contemporary women and men.

Excerpted from https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/red-book-of-carl-jung/the-red-book-and-beyond.html where you can read more about Carl Jung, his life and his work.

Oh my... have been out of this loop for a very long time, but am grateful for the inspiration that urged me to open this email. This is a lot. So many questions have opened up for me as I read this beautiful writing. I love the analogy of trying to piece together pieces of a puzzle (because I love puzzles) and felt a sense of relief in the question, "what if the puzzle is not (or never) finished"? Don't we all try to put the pieces together to make sense of our lives? Perhaps not, but I do. It actually becomes a magical sort of exercise, but yes, there will always be more spaces and pieces to fit... and so it goes.

Amy! So grateful for you, and your words.